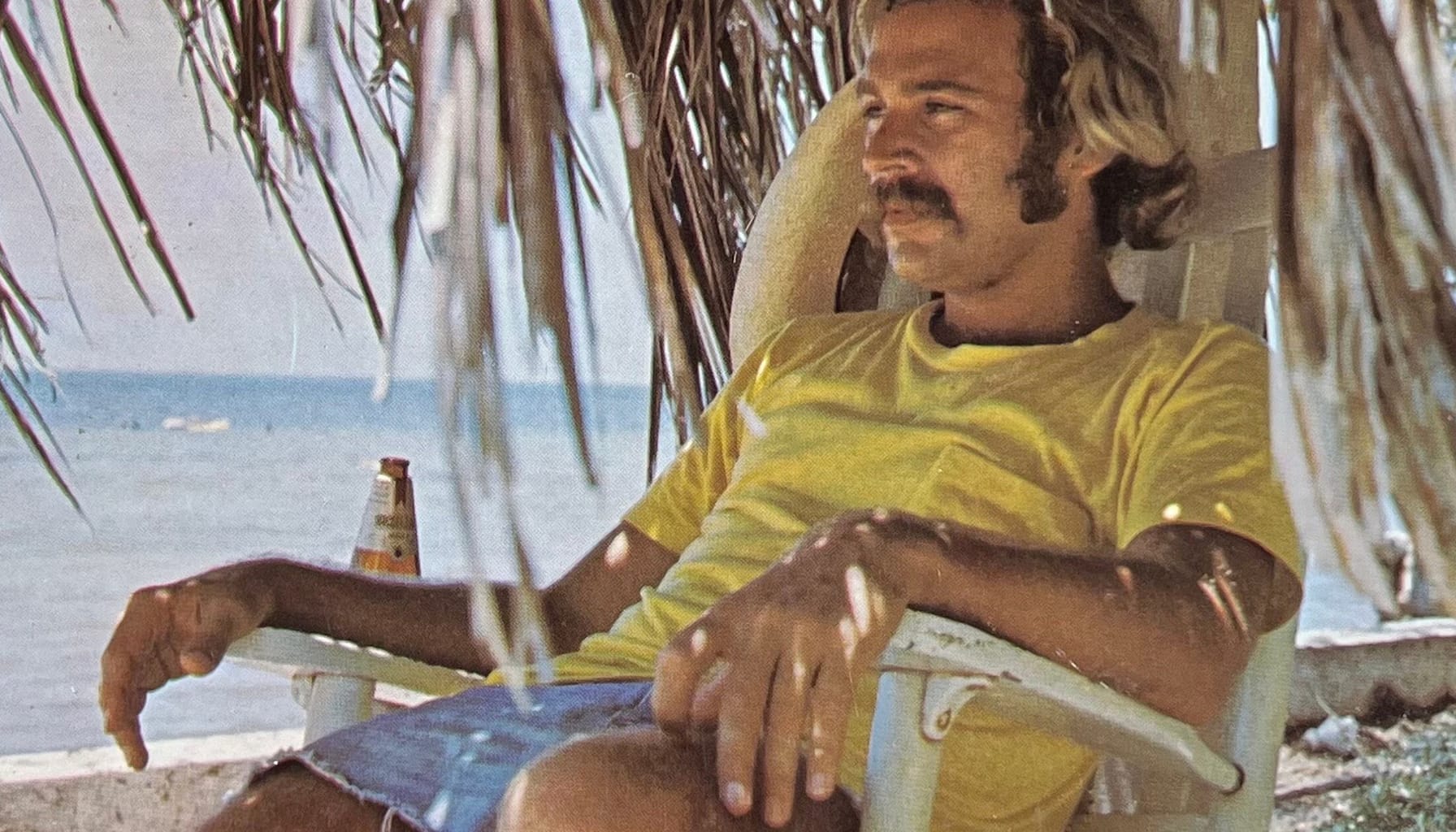

Blindspotting: Jimmy Buffett, "A-1-A"

Wasting away, and then wasting some more

The Legacy: Today, his name has long since become synonymous with "musicians who've turned themselves into lifestyle brands," but for the first few albums of his career, Jimmy Buffett was sort of a nobody. That started to change with the release of 1974's A1A, which found him with the full heft of ABC/Dunhill's promotional might behind him, albeit for rather ghoulish reasons. (Following Jim Croce's tragic death, the label allegedly saw him as a potential replacement.)

Buffett's ABC tenure roughly coincided with his move to Key West, and A1A was the third in a series of records that reflected his new tropical environs — and the first that hit any kind of commercial paydirt, peaking at No. 25 on the Billboard 200. It still wasn't enough to spur gold or platinum record sales, but it was a harbinger of things to come; by the end of the decade, he was a regular fixture in the Top 20, with the sales certifications to match.

First Impressions: If you aren't the type of person who has a fetish for steel drums and beachy twang, Jimmy Buffett is probably not your cup of tea and/or margarita. I'm 100 percent in the "not" category, and have spent much of my life strenuously avoiding his various paeans to getting loaded and relaxing in the sun, but I have to admit that a lot of my antipathy has always stemmed from the army of aging yuppies that dubbed themselves "Parrotheads" and clogged his concert crowds for decades. Tropical anthems have their place, but when they're being used as the basis for a multimillion-dollar enterprise that encompasses everything from middling beer to resorts, I feel like it's the thinking person's duty to look askance. Since I try to be a thinking person as often as possible, askance I have looked.

All of which makes Jimmy Buffett a natural pick for this series. Much as it pained me to contemplate spending a day with one of his albums, I recognized the time had come, so I hit up Antagonistic Friend of Jefitoblog, cherished Record Player listener, and avowed Buffett fan Velvet Rebel for an entry point recommendation, and he told me to start with A1A. Here we are.

First off, I want to say that I appreciate Velvet Rebel pointing me in this direction. Even though A1A is the third in Buffett's "Key West" series of recordings, it captures him at a formative moment; two records later, with Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes, he finally went platinum. Here, in other words, we hear the tectonic plates of Buffett's mighty sound beginning to lock into place, and for me, that makes it a better introduction than anything that was released post-Changes.

At first listen, A1A comes across as something an Eagles fan might have tossed on the turntable during gaps between release cycles. It has a generally sleepy quasi-country feel, with plenty of lap steel and some downright Eagles-like backing vocals on the closing track, "Tin Cup Chalice." It's also pretty consistent, if you're into this sort of thing; for a spin or two, I wondered whether I'd even have much to say about it.

But the more I listened to A1A, the more annoyed I became.

I want to stress that everything I've already said about the album still applies: It's competently written and performed, resolutely pleasant, and extremely easy to listen to. Placed within the context of the very mellow singer-songwriter scene of the early '70s, it makes total sense; you can absolutely understand why it was Buffett's highest-charting album to that point. I'm not going to go back and listen to his earlier stuff, so I can't say whether this was a case of the artist deliberately refining his sound in pursuit of sales or simply catching the zeitgeist by accident, but I can tell you that if you were a fan of Jackson Browne or Bread or America or any of the other similar-sounding acts during this era, A1A slots in so easily that it might as well have been machine-tooled to do so.

But it's by placing it within the context of its era that I start to get irritated with A1A, and Buffett in general. In the decades following its release, he'd become much more annoying by molting into an avatar for the "life's a beach" crowd, reaping astronomical sums of money by hoovering it up from garishly clothed golf bros and their rosé-guzzling girlfriends, wives, and mistresses. Early Buffett is obnoxious on a quieter level, but it's still one that points to the ways in which his music exists at the intersection of post-Vietnam disillusionment on the left and right sides of the American political spectrum.

I know this sort of highfalutin windbaggery isn't the type of thing you all tend to expect from these posts, so I'll try to keep it brief. On the left, you've got a group of people who've looked on in horror while nearly 60,000 American soldiers died in an unwinnable, unethical, and utterly unnecessary war, all on top of a series of brutal assassinations and the slowly administered poison of the Watergate scandal. On the right, you've got a group of people who've looked on in horror while wave after wave of disaffected and marginalized citizens have demanded their place at the table, all while government at every level has expanded to strengthen the social safety net. In the background, there's the low hum of the Cold War, seeping the dread of communism and nuclear holocaust into the national psyche.

People dealt with this in all sorts of ways, but broadly speaking, as I said before, there was a lot of disillusionment. On the left, some of that fed into a growing affection for the idea of checking out of society, albeit not in the utopian way commonly associated with the hippies; instead, these folks started to get cynical, and gravitated toward idealized rogues who bucked the system by breaking whatever rules they could get away with. I don't think it's any accident that shortly after A1A was released, Buffett provided the soundtrack to Rancho Deluxe, a (quite good) dramedy about a pair of Montana cattle hustlers. It's also no accident that A1A's best-known track, "A Pirate Looks at Forty," romanticizes the life of a smuggler with a heart of gold just a few years before Smokey and the Bandit made a box-office mint, Han Solo became a hero to generations, and The Dukes of Hazzard taught us that the only thing cooler than pissing off your local sheriff was learning how to slide across the hood of your hot rod. Whether intentionally or not, he was tapping into a toxic groundswell.

On the right, there was the rise of the Marlboro man, a ruggedly independent spiritual cowboy who just wanted to be left alone so he could live off the land and contemplate simpler times. This is the sack of shit that Ronald Reagan handed out to American families during the 1979 election, and 40-odd years later, a whole bunch of U.S. citizens are still in slack-jawed thrall to its mythical splendor. I could go on, but it would just turn into a rant; you get the point.

So how in the world does this relate to Jimmy Buffett's music? To listen to A1A — and, presumably, the rest of his catalog — is to subject oneself to story after story about guys who lead fantasy lives of perpetual self-administered anesthesia (to quote "A Pirate Looks at Forty," "I have been drunk now for over two weeks") while lining their pockets through morally ambiguous means and yearning for their younger days. I'm being very broad, but in my defense, so was Buffett; if there's one thing that ties his songs' protagonists together, it's that they aren't interested in working for anything, whether it's money or personal growth. The savage irony here is that Buffett's music is lazily aspirational while also being stubbornly unconcerned about the future. The closest he comes to feeling anything about anything is when he briefly mentions almost dying in a real-life car accident. Unintentionally, he serves as the link between faded hippies and MAGA bros by endorsing disconnection and indulging in nostalgia as healthy responses to trauma.

It's well worth pointing out that there's a real and obvious appeal in Buffett's fantasy, and again, if all you want is something to have on in the background, this record goes down about as easy as a bottle of his middling Landshark lager. There was a time when I was baffled by the mystery of how Buffett attracted his legions of self-described Parrotheads, but now that I've actually spent time with one of his records, I feel like I understand it to an uncomfortable degree. The world can be a frightening place, and living in it can be soul-deadeningly stressful; if we are to make it a better place, we can only do so through the difficult and scary work of connecting with others in an ongoing effort to better understand the scope of the human experience. It's so much easier to unplug, especially when you're being given the message that those efforts are a waste of time and energy. It's comforting to be coddled in this way, no matter how smug and solipsistic the meaning behind the message might be.

Favorite Song: Since I'm forcing myself to choose, I guess I'll go with the leadoff track, "Makin' Music for Money," a cover of the Alex Harvey song about putting one's creative joy ahead of any attempt to turn it into cash. One might argue that it's heavily ironic that Buffett was drawn to this song, given how much money he made with his music, but on the other hand, for much of his career, he was making so much money through other revenue streams that he really didn't have to worry about selling records. Maybe there's a moral to that story somewhere, but I'm too tired to see it.