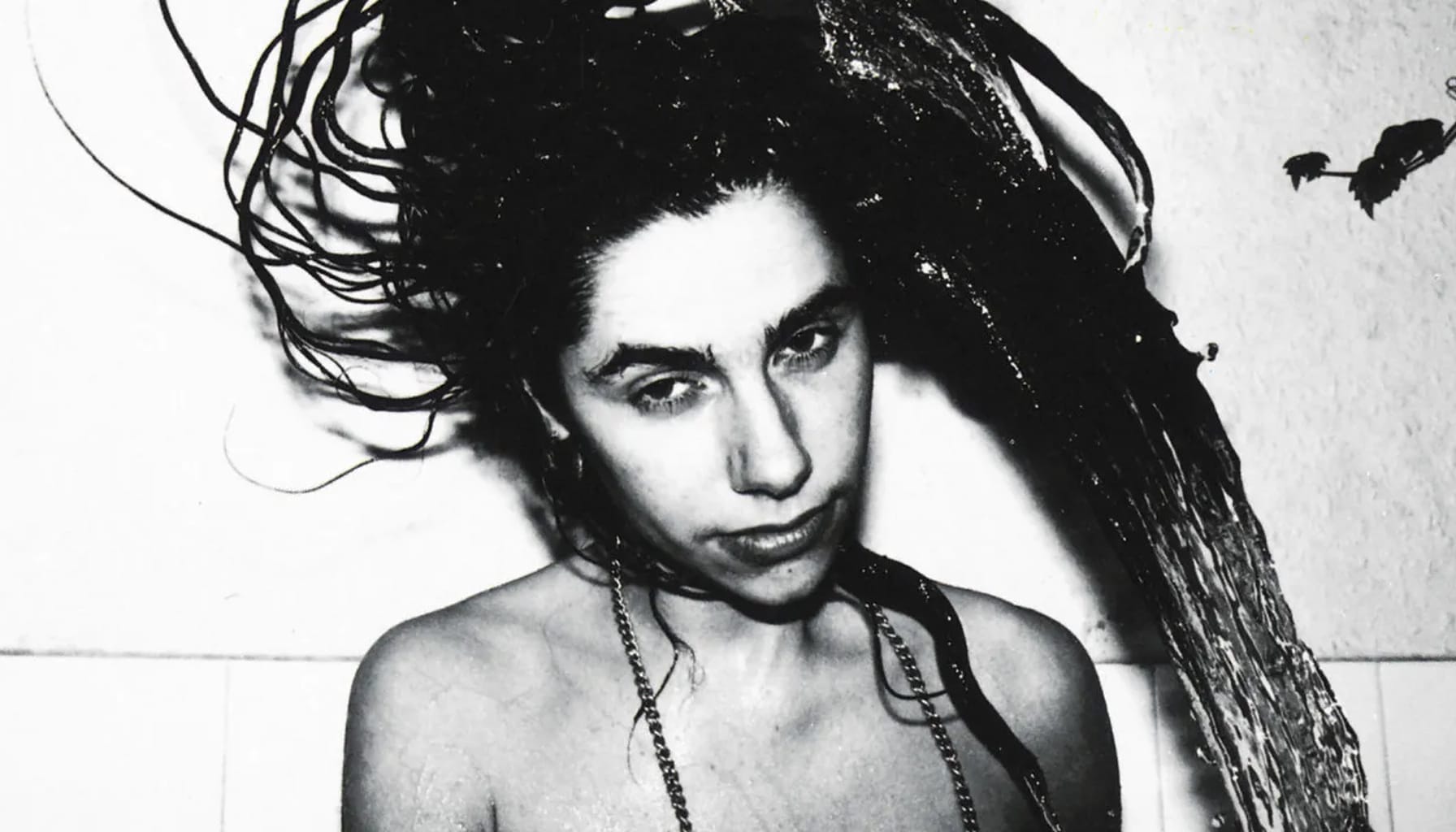

Blindspotting: PJ Harvey, "Rid of Me"

Fixing musical blind spots, one album at a time

The Legacy: PJ Harvey — at that point still the name of a squall-surfing power trio as well as its lead singer and songwriter — were already hot shit, critically speaking, when they released their sophomore outing in late April 1993. Their first album, 1992's Dry, earned raves in the States as well as Harvey's native UK; although it didn't chart here, the stage was clearly set for further plaudits upon their return.

To Harvey's credit, even though it arrived just about a year after its predecessor, Rid of Me isn't Dry 2.0 — instead, the band hooked up with producer Steve Albini to deliver a more aggressive and sonically bare-bones set of songs, one whose unabashed anger and raw, gunky power just so happened to align pretty perfectly with the wave of increasingly unadorned records emerging from the aftermath of the Nevermind/Ten atom bomb.

Rid of Me's sales numbers didn't come anywhere near those albums — it topped out at No. 158 on the Billboard chart, and neither of its singles charted, even at alternative stations — but the overwhelmingly positive critical response cemented Harvey as one of the era's most acclaimed songwriters, earning praise from an eclectic assortment of her peers in the process. Elvis Costello, for example, appreciated what he heard as recurring themes of "blood and fucking" in her work. (Harvey, in response: "He's wrong.")

Whether or not they're doing it intentionally, records that evoke "blood and fucking" are generally not destined for major commercial success, and that would continue to be the case for Harvey; although Rid of Me catapulted her to name-brand status, the remainder of the decade saw her continually flirting with sales in the 350,000-copy range here in the States. These are numbers a lot of acts would kill for, of course, but they also underscore Harvey's general deal — an artist whose generally accepted importance eclipses the cultural penetration achieved by her art.

First Impressions: There are albums that exist to entertain, and albums that exist because the artist needed to make them. Rid of Me sits solidly on the latter end of the spectrum. This is not to say it isn't entertaining — I mean, I personally wasn't particularly entertained, but your mileage may vary — it's merely to frame expectations by noting that from its often rather inscrutable lyrics to the dry heat of the music, this is a record that is more concerned with its own existence than the listener's response to it.

This kind of thing can be deeply rewarding, particularly if you happen to be on the artist's wavelength; there's nothing quite like consuming a piece of art and coming away feeling like you've been seen and heard. Rid of Me had its finger on the pulse for a lot of people in the early '90s, and although this type of observation is usually followed by something about it being an angry feminist record, I think it's important to note that Harvey herself resisted being wedged into that box. It would be impossible not to hear those themes throughout the album, but that isn't the only reason it was so timely; listeners of all persuasions were hungry for a more direct approach to studio sound after a decade of increasingly ornate and/or tech-dependent production, and so were many musicians. Albini later said he played Nirvana some Rid of Me mixes while they were in discussions for In Utero, which is the kind of trivia you almost don't need to learn in order to know it; it also explains, as well as anything could, the way Albini's approach here laid a template for many of the rock records released throughout the remainder of the decade.

All of which is to say that while Rid of Me offers very little of what I want in an album, it would be churlishly ignorant to pretend it has nothing to offer. I can appreciate what I hear here even if it doesn't check many boxes for me — it's hard not to admire a work that's this stubbornly insular, one that feels like it was written and recorded as a compulsive act, a necessary purging, made without a single thought for how it might be received by anyone else in the world. The tight focus held by Albini's recording perfectly matches the songs; everything is so close that it feels like you could suffocate in it, which seems like precisely the point.

Hidden Gems: It's always hard to think about "hidden gems" in the context of a record like this, one that's been heard by relatively few people but loved to death by most of those who have. Is it fair to say that any track could be called a hidden gem, or is that ridiculous, given that every track's been pored over obsessively by thousands? I don't really have an answer to that, but I dig the slide guitar parts Harvey came up with for "Dry," which are simple, coolly melodic, and just sloppy enough to retain the right amount of attitude. Ry Cooder would approve, I think, and he doesn't approve of much.