Major Letdowns: Loverboy, "Wildside"

Loverboy were one of the most successful rock bands of the '80s... until they weren't

Very few musicians manage to make it big enough to sign a recording deal with a major label — and fewer still are lucky enough to spend their entire career at that level. Major Letdowns takes a look at studio albums that ended up banishing the artists who recorded them from the major-label ranks, never to return.

Aside from "Working for the Weekend," their so-dumb-it's-brilliant ode to taking this job and shoving it for 48 hours, Loverboy has been largely forgotten over the last few decades — to the point that it may come as a surprise that they were objectively one of the most commercially successful rock acts of the '80s, releasing four straight multi-platinum albums between 1980 and 1985 while maintaining an impressively regular presence on the Top 40 alongside the requisite string of rock hits. While you aren't necessarily likely to hear them on classic rock stations today, songs like "Turn Me Loose" and "Hot Girls in Love" were hugely popular in their day.

Loverboy's big, fat hot streak isn't something I've really spent much time thinking about; as a result, I was left unexpectedly disoriented after looking at their sales history while prepping for this post. It was definitely a decade of musical bombast, and this band's music was nothing if not big and dumb, so it stands to reason that they'd find an audience — but ten million units sold? How? Why?

This isn't (just) a cowardly act of hiding behind years of changing musical trends in order to lob easy potshots at an act whose sound happened to fall out of favor. Loverboy's music checked all the boxes you had to fill in order to get on the radio at the time, but they weren't doing anything their peers didn't do better. Pick any random major rock band from the era — Foreigner, Survivor, 38 Special — and try to argue that Loverboy's hits were more interesting in any way. There isn't anything wrong with being basic, but even at their peak, that's all their records ever were. If they got clever enough to rhyme "hero" with "zero," it was a really great day at the Loverboy lyrics factory.

"Factory" is an apt word to use, and not just because these guys were a prime example of the sort of faceless corporate rock that ended up becoming emblematic of the era's worst musical inclinations. If they were extremely basic — heck, probably because they were so basic — they were also very consistent, releasing a new album every 12-18 months, each one fully stocked with an array of shout-along anthems built with big, block-shaped hooks. If they didn't have it in them to surprise you, they were at least willing to bring you more of exactly what you were expecting from them.

If it's difficult to understand how Loverboy became so popular in the first place, it's also hard to trace the fault lines that eventually cratered their major-label tenure. When they released their fifth album, Wildside, in September of 1987, they were, by all appearances, hotter than ever — frontman Mike Reno teamed up with Ann Wilson of Heart to record "Almost Paradise" for the Footloose soundtrack in '84, a massive hit that led directly into 1985's Lovin' Every Minute of It, which led in turn to the group recording "Heaven in Your Eyes" for the Top Gun soundtrack in '86. By all rights, Wildside should have been just another platinum widget off the assembly line.

It's true that signs of decay were starting to appear on the hairspray-coated scaffolding that propped up the AOR of the era — Night Ranger, for example, suffered the first knee-skinning of their career with Big Life in 1987 — but it isn't like this style of rock was really becoming that much less popular. I can remember an article from late '87 that suggested "urban" sounds were starting to gain in popularity, which is also true to an extent, but even as the acts in Loverboy's peer group started showing their age, they continued to crank out huge hits into the early '90s. Reno is one of many formerly famous dudes to try and pin his commercial downfall on grunge, which is just lazy scapegoating; by the time Nirvana topped the charts, Loverboy had long since broken up.

So what turned people away from this band, and Wildside in particular? Well, the leadoff single might have had something to do with it.

The first thing I want to point out about this breathtakingly stupid song is that it took five people to write it: Reno, guitarist Paul Dean, prolific rock co-writer Todd Cerney, and Jon Bon Jovi and Richie Sambora. According to Dean, Bon Jovi and Sambora earned their credits courtesy of a writing date that apparently produced several songs, one of which included the "na-na-na-na" hook you hear here. Dean airlifted that bit into a different song he worked on with Reno and Cerney, which became "Notorious." (Bon Jovi would pick up another co-writing credit through similarly non-organic means a few years later, when Arista president Clive Davis forced Daryl Hall to crowbar some stray JBJ bits into "So Close," the leadoff single from the album that ended Hall and Oates' major-label career. Career suicide, thy name is Jon.)

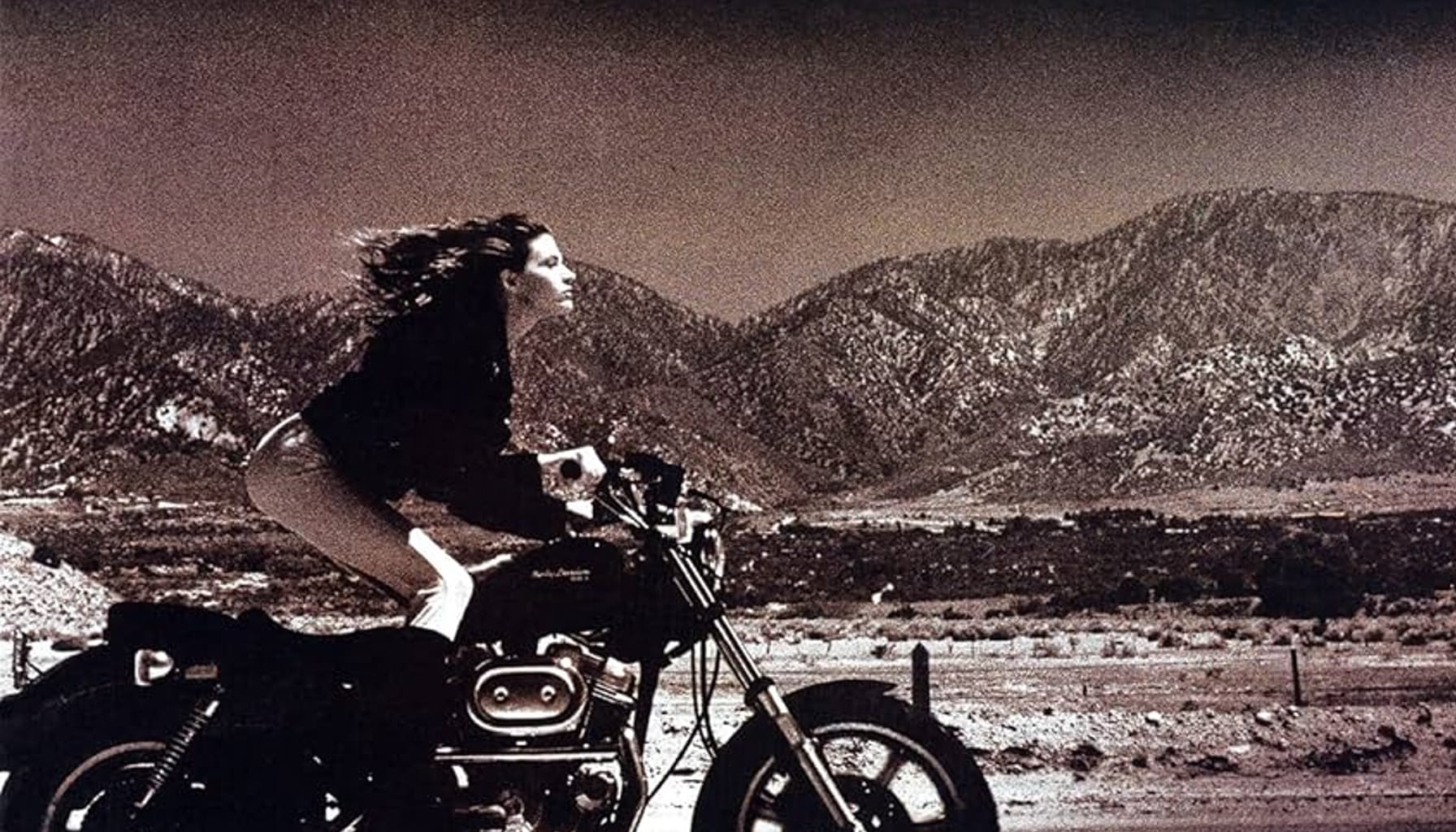

Sometimes, you can't tell when a song was cobbled together this way — the Beatles were generationally brilliant when it came to snapping musical puzzle pieces together — but "Notorious" sounds exactly like the sloppy hash it is, a horny bellow from the third or fourth ring of late '80s AOR hell whose desperate attempts to generate excitement only make you feel bad for the band. Director David Fincher, hired for the video before he became too famous to take this type of gig, met the material halfway by delivering a clip that's just as leering and witless as the song itself, and I suppose there's a certain sort of honor in that. I mean, when you're handed a track that includes the lines "Señorita solitaire / You've got a certain kind of savoir faire" and "Every mother's nightmare, every schoolboy's dream," there's no point in pretending you don't understand the assignment.

"Notorious" did fine at rock radio, and it squeaked into the Top 40, which was really no big deal for Loverboy, at least on paper; at this point, they'd established a long history of releasing singles that were bigger rock hits. The real problem was that it was far and away the most radio-friendly cut that Wildside had to offer — a deficiency brought into stark relief when Columbia released "Love Will Rise Again" and "Break It to Me Gently" as follow-up singles, neither of which charted at any format.

I want to pause for a moment to make it clear that when I say this album had a deeply lame first single and a track listing stuffed with subpar choices for follow-ups, I'm not saying it's very different from any other Loverboy album you could pick to listen to. Songs like "Break It to Me Gently" and "Don't Let Go" are dunderheaded wads of ground chuck, but in the context of the group's discography, they don't represent a significant drop in quality. At the time, a lot of critics credited Wildside with getting the band "back to its roots" by focusing heavily on rock songs instead of ballads, and they weren't necessarily wrong. I will say that I find the production awfully grating, but it's grating in the same way a lot of rock records were at the time — when I tell you that Wildside was produced by Bruce Fairbairn, mixed by Bob Rock, and engineered by Mike Fraser, I'm telling you every single thing you need to know about the way it sounds. Even when they tried coloring outside the lines, like tossing in some harmonica on a few songs or adding a fat, farting sax solo to the title track, it all gets mashed into the same monochromatic cube of power chords and yelling.

Ultimately, if audiences seemed to be getting a little tired of Loverboy's shtick, their sudden lack of interest may have been well-timed, because the guys in the band were also getting sick of each other. Although Wildside still went gold, after the album peaked at No. 42 and subsequent singles went nowhere, the group took a look at the writing on the wall and broke up the following year. They reunited briefly to do some promo dates for the contract-fulfilling best-of set Big Ones in 1989, then broke up again — only to reunite again in '91, officially beginning a new era in which they would spend far more time touring and putting out compilations than working on new material. (Their most recent releases, 2012's Rock 'n' Roll Revival and 2014's Unfinished Business, consist largely of re-recorded hits and exhumed/polished demos, respectively.)

All told, I think it'd be hard to argue that any kind of injustice occurred when Columbia dropped Loverboy. Even without the looming sea change that upended rock radio in the '90s, it's difficult to imagine a world in which this band's loudly reductive aesthetic needed more time to develop — they did what they did with appropriate levels of confidence and volume, and five albums feels like just about enough of it.