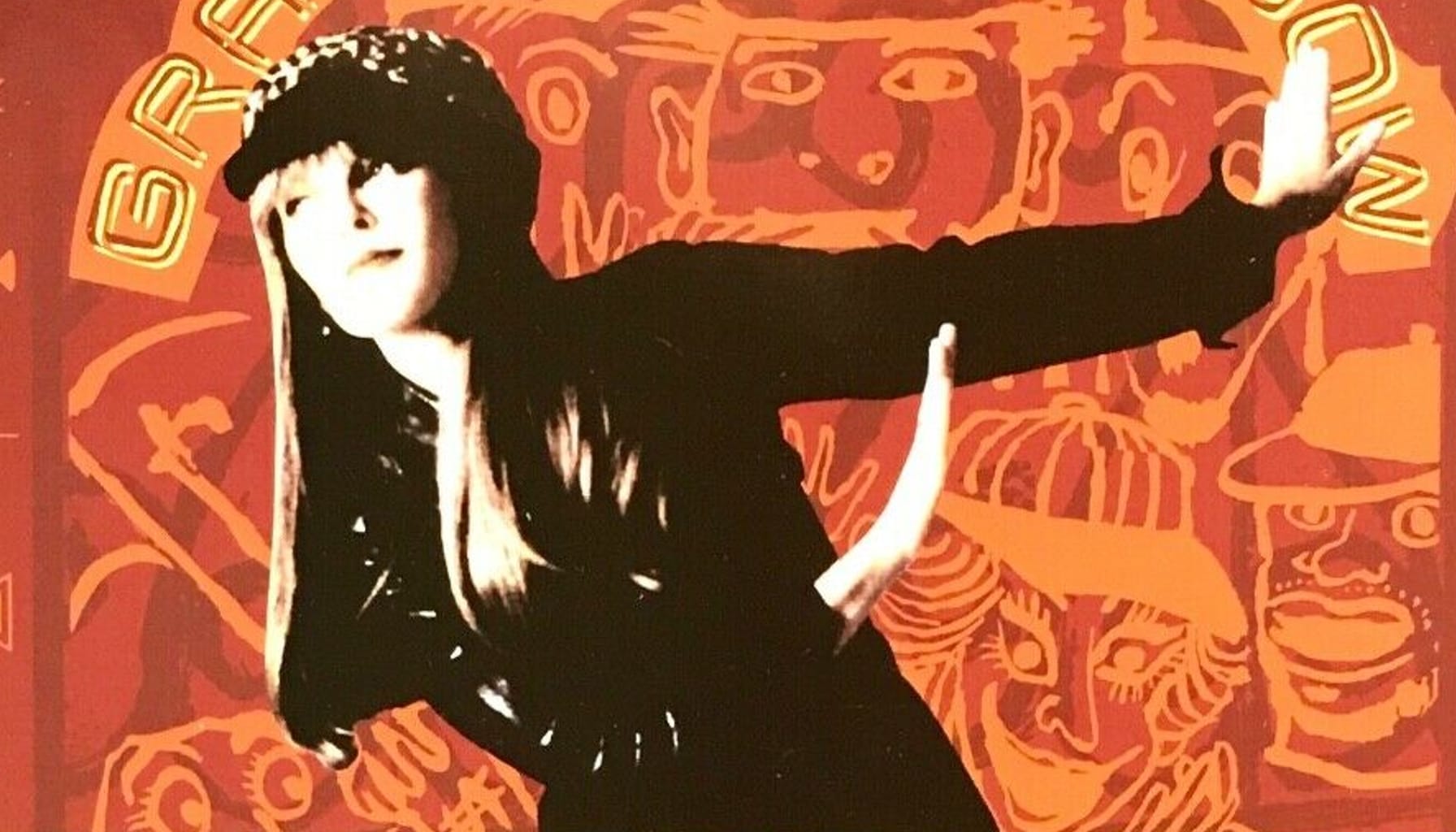

Major Letdowns: Pat Benatar, "Gravity's Rainbow"

She hit us with her best shot, but in 1993, it wasn't enough

I don't know if it's ever truly appropriate to call a member of a hall of fame "underrated," but it kinda feels right where Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee Pat Benatar is concerned. Despite being one of the more prolific and consistent hitmakers of the '80s, she was shuffled off to the state-fair margins with a quickness once her sales started flagging, and she's never really been granted the sort of "hey, this artist is actually pretty great" reappraisal that tends to come with post-peak persistence.

Aside from being a fixture on pop and rock radio for roughly a decade, Benatar was something of a trailblazer. She was famously the first female artist to have a video played on MTV, and although she wasn't the first hard-rocking woman to have a commercially successful recording career, her string of hits certainly paved the way for plenty of other acts. On a non-musical note, she was also a fashion icon, as noted in this (NSFW) clip from the timeless Fast Times at Ridgemont High:

Between 1979 and 1988, Benatar peeled off 15 Top 40 hits, four of which went Top Ten — but with the benefit of hindsight, I think it's pretty clear that she was ultimately a victim of her own success. Although most of her singles were penned by outside writers, they were still, by and large, punchy rockers that aligned well with her deeper cuts (typically written by Benatar's husband and bandmate, guitarist Neil Giraldo, in conjunction with an array of collaborators that frequently included drummer Myron Grombacher). But as those hits piled up, Benatar's label grew more invested in maintaining her success, and her singles grew progressively poppier as the decade wore on. By the time she released 1985's Seven the Hard Way, synths had started to overpower the guitars; in that context, her final Top 40 hit, 1988's "All Fired Up," was viewed as a return to roots even though it's about as slick as anything else from that period.

To her credit, Benatar could not only sense her own creative stasis, she was willing to do something about it — even if it meant holding her label over a barrel. "It was a hostage situation, really," she said in 1993. "They didn't have a choice. My contract was pretty much up at that point and it was, 'If you don't let me do this, I'm going to CBS.' You know? So they said, 'No problem!'"

The "this" she was referring to took the form of her eighth studio album, 1991's True Love, which shook free from the established Benatar formula by collecting a pack of blues standards, adding a few originals, and bringing in the Roomful of Blues horn section for extra color. It was still a Top 40 record — in fact, in terms of chart placement, it didn't do much worse than its predecessor — but it was still an act of commercial suicide, albeit one that maintained her credibility at rock radio, where the album's fine but unnecessary cover of "Payin' the Cost to Be the Boss" went Top 20.

Cutting a jump blues LP failed to add another gold or platinum award to her collection, and one suspects it may have also burned a bridge or two with some folks at the label, but it re-energized Benatar, who had something of a creative epiphany after stripping away all the layers of production that had come to define her work.

"You had an idea of what it was to be a rock 'n' roll band and you kind of boxed yourself in and people on the outside were boxing you in," Benatar told the AP. "The thing about the blues record was that once that happened, I knew there were no more boxes. I knew that's what rock 'n' roll was really about."

It was this state of mind that helped produce Benatar's next album, which is the one we're here to talk about today. Released in May of 1993, Gravity's Rainbow drew a hard line between Benatars past and present, not least by virtue of a track listing completely devoid of songwriting input from anyone outside the band. Benatar herself co-wrote seven of the record's 12 tracks — including leadoff single "Everybody Lay Down," which honestly kind of kicks ass.

Unfortunately, "Everybody Lay Down" — and the rest of Gravity's Rainbow — faced some pretty stiff headwinds. For starters, there was the elephant in the room facing every established rock act in the '90s: Public demand for new music from pretty much all of those artists plummeted toward the start of the decade, leading most labels to half-heartedly play out the string on existing contracts by fulfilling guarantees without adding much in terms of promotion. Even though they were often treated like fake rockers in the '80s, female artists weren't exempt from the embarrassing fates that befell male peers like the guys in Warrant, Poison, Winger, et cetera.

Female artists were — and have always been — held to a different standard in terms of age, however. While reviewing press clippings for Gravity's Rainbow, I was kind of surprised to see how much of an emphasis was placed on the fact that Benatar was 40 at the time of its release. I probably shouldn't have been surprised — from the dawn of the rock era, 40 was viewed as a sort of harrowing rubicon that would sap the vitality from any artist who dared cross it — but either way, it couldn't have helped her odds of working her way into heavy rotation at pop radio.

Either of these issues might have been surmountable with enough of a heavy push from the label, but Benatar was snake-bitten here as well: Her longtime home, Chrysalis Records, was just on the other side of a sale to EMI, with a dwindling roster of acts whose most impressive sales totals were all in the rear view mirror. Their biggest name, Huey Lewis, asked for (and was granted) the opportunity to fly the coop for EMI in 1990; by the time Gravity's Rainbow came out, the Chrysalis imprint was in the midst of a string of chart disappointments that included Sinéad O'Connor's scandal-plagued Am I Not Your Girl? and would soon grow to encompass Billy Idol's infamously misguided Cyberpunk. Needless to say, their ability to break new artists, or get top sales out of artists they'd already had success with, was at a low ebb.

Combined, all of these factors conspired to thwart the sales campaign for Gravity's Rainbow before it even had a chance to get started. "Everybody Lay Down" was a solid hit at rock radio, but that didn't do much of anything to move units, and given that she hadn't toured since 1988, she was also starting over in terms of the venues she could fill; ultimately, the album peaked at No. 85, which was the worst showing of Benatar's entire career by a wide margin.

I'm sure some at the label felt Benatar hurt her commercial prospects by detouring into True Love, but I'm not so sure about that. If anything, I'd wager that peeling back the synths and skipping the power ballads on that album was a credibility-saving move; if she'd released another pop record in 1991, she'd have been that much easier to dismiss when things really started to change in the rock market. Of course, as I noted earlier, she ended up being dismissed pretty quickly anyway, which remains perplexing to me.

Like pretty much every other rock artist in her peer group, Benatar signed with CMC in the '90s, where she released one album — 1997's little-heard Innamorata — before going the full-on indie route with 2003's Go, which remains her most recent full-length release of new material. It seems pretty likely that she looked at the uphill battle she was suddenly facing in the marketplace, shrugged, and decided there wasn't much of a point in doing anything other than booking tour dates — which is a shame if for no other reason than it would have been really interesting to hear what she would have gotten up to as a recording artist aging into her 50s, 60s, and 70s on her own creative terms.

There may yet be hope, however. While I'd be surprised if they ended up signing to a major — what would be the point in 2025? — Benatar and Giraldo told Billboard last year that they have a pile of songs that have never been recorded; it's just a matter of finding the time, which seems unlikely to present itself while they're tinkering with their stage musical Invincible, which apparently uses Benatar's songs to retell the story of Romeo and Juliet. As she put it, "We have about 125 songs around, waiting to be recorded. If you can get my husband in there to do it, please be my guest."