Revisiting SPIN's 1993 New Music Preview

From the Buzz Bin to the cutout bin

We watched the '80s start to truly become the '90s when we went through the 1991 New Music Preview, and watched the grunge bomb explode all over the 1992 New Music Preview. Now it's time to take a look at SPIN's predictions for 1993, which unfortunately saw the magazine continue to get safer with its picks while devoting even less space to the issue's main feature. (It's just about matched for page count with the cover profile on Arrested Development.)

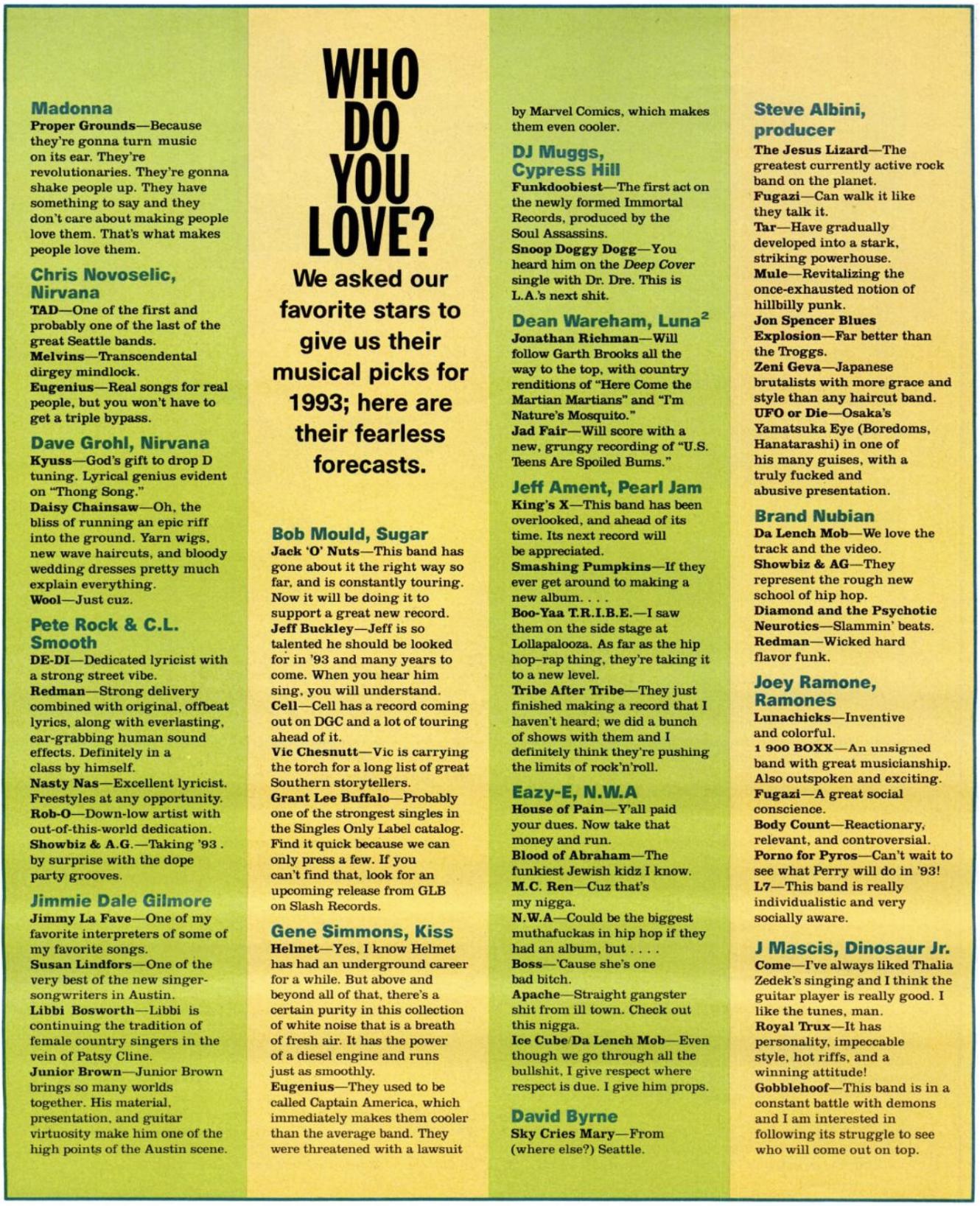

One cool twist to this issue, though: The staff rounded up breakout artist selections from a bunch of well-known musicians, which were too numerous to cover individually, but are still well worth looking over. I'll include those at the end of the post.

Flop - Their brief writeup describes their sound as "ungrunge," which is accurate enough, I suppose, although in retrospect, it's probably more illustrative of the trends that were emerging at the time. Flop were basically an early '90s power pop group — not as overtly sticky-sweet as the Greenberry Woods, and not as ornate as Jellyfish, but still wholly focused on writing fun, catchy songs. This was enough to land them a deal with Epic, but — as was so often the case for bands beckoned out of the indie ranks during the '90s alterna-gold rush — it wasn't enough to sustain the label's interest. By the time Flop's 1993 release Whenever You're Ready landed in stores, they'd lost whatever muscle had been waiting to be flexed on their behalf, the record (cough) flopped, and they were soon released from their contract. It's a shame; Whenever You're Ready is a lot of fun, and it's tempting to imagine a world in which Flop didn't break up in '95.

Drive Like Jehu - The '90s were the last decade when the record industry really mattered, and the decade's early years represent the last time label execs fell all over themselves en masse to sign anything that sounded even remotely adjacent to whatever was selling copies for their competitors. This produced a lot of hits, but it also churned up a ton of fascinating chaos that people tend to forget when they skip from Nirvana to the Gin Blossoms to Britney Spears — there are a ton of acts who signed major-label contracts during this period, but probably wouldn't have stood a chance of attracting that type of interest at any other point in time. The short-lived Drive Like Jehu is a fine example: Scooped up by Interscope after releasing their self-titled debut in 1991, they were a wildly skronky group who never had a prayer of being played on any but the most staunchly, aggressively independent college stations. They were also destined to fade out quickly, as lead guitarist John Reis drifted more toward his other band, Rocket from the Crypt.

These days, Drive Like Jehu are credited with helping lay the groundwork for emo, which doesn't strike me as something a person should be proud of, but to each their own. For me, the most entertaining thing about listening to their sole Interscope release, 1994's Yank Crime, is imagining someone at Interscope trying to figure out what the hell to release as a single.

Freedy Johnston - An artifact from the days when releasing a collection of well-written singer-songwriter stuff was enough to get you noticed by the Village Voice, which in turn was enough to get major-label A&R guys knocking on your door, Freedy Johnston definitely seemed poised for greater success in 1993. His 1992 album Can You Fly, recorded using money he earned by selling off part of his family's Kansas farmland, presented an artist wise beyond his years — a sort of loose sonic blend of Neil Young and Marshall Crenshaw, with piercing lyrical insight and an utter lack of pretension. The widespread critical praise heaped on Fly helped Johnston land at Elektra, where he enjoyed an early burst of medium success (1994's "Bad Reputation" almost reached the Top 40) before settling into the background as a prestige signing whose subsequent releases sold next to nothing. (Something else that hardly ever happens anymore.)

It's easy to understand the major-label interest in Johnston, although one suspects the Elektra brass might have signed him hoping he'd give them stuff they could regularly get on the radio. I feel like it's safe to assume they saw Can You Fly as the bare-bones template for what Johnston could achieve with bigger recording budgets, which wasn't really the case; for better or worse, his whole deal is laid out pretty clearly with those 13 tracks.

Kelly Willis - Kelly Willis' writeup describes her as "un-Garth," which — well, everything I said about Flop being "ungrunge" applies here too. It seems unlikely to me that Willis appreciated it at the time; while it's true that she wasn't peddling Garth Brooks' particular brand of arena-ready country, neither was she doing anything particularly different. Perhaps the main difference, aside from the massive gap in sales numbers between the two, is that Willis had better taste in outside material by name acts: Brooks appeared on a Kiss tribute album and covered Billy Joel's "Shameless," while Willis recorded songs written by Marshall Crenshaw, Jim Lauderdale, Paul Kelly, Joe Ely, Steve Earle, and Kevin Welch. (Bonus cool points for enlisting the guys in Jellyfish to contribute background vocals on her third album.)

SPIN also described Willis' music as "libidinal," which probably gets at the heart of why her major-label tenure was over after three years and just as many albums. She's strikingly pretty and has a voice that could punch a hole in the side of a mountain, so naturally, the former tended to be the focus at the expense of the latter; according to her Wikipedia page, she was "uncomfortable with the way she was marketed" during this period, which seems like an extremely polite euphemism for a dynamic we all know far too well. After opting out of her contract with MCA, she went the indie route, which she's maintained to consistent critical acclaim.

Whatever the sordid details, the one thing we know for sure is that Willis' MCA releases didn't sell half as well as they should have. How was this single anything less than a hit?

Mercury Rev - Similarly to Drive Like Jehu, it's hard to imagine any rationale behind the industry's interest in Mercury Rev that didn't begin and end with "We don't get it at all, so this is probably something kids will like." Perhaps best known for their lengthy loose affiliation with the Flaming Lips — guitarist Jonathan Donahue was a member of the group for a time, and bassist Dave Fridmann has co-produced 11 of their albums — Mercury Rev started out as an experimental collective whose music was chiefly intended to serve as the soundtrack for the members' student films, which goes a long way toward explaining the often inscrutable patchwork of noise that erupted from their first two albums. If it's funny to imagine someone at Interscope trying to sift a single out of the jagged wreckage of Drive Like Jehu's Yank Crime, it's downright hilarious to imagine the folks at Columbia listening to Mercury Rev's Boces in search of something to send program directors.

This era in the band's sonic history is brief — lead singer David Baker was either fired or quit after the Boces tour, at which point Mercury Rev's blend of psychedelic noise rock started to bend more heavily toward the "psychedelic" side of that equation; by the end of the decade, they were experimenting with rootsier sounds, and working with Levon Helm and Garth Hudson of the Band. All of which is to say that these guys have had a fascinating journey, albeit one I feel fine about choosing not to follow.

Afghan Whigs - I'm sure it didn't actually happen this way, but it's amusing to imagine a world where the folks at Elektra signed the Afghan Whigs without even listening to their music, simply by virtue of the fact that they were a Sub Pop act when Nirvana went nuclear. Setting cheap cynicism aside, the reality is that Elektra was a great place to be if you were a left-of-center rock act in the '90s, and unlike many of their peers, the Afghan Whigs flourished — at least in terms of acclaim, if not huge sales — after going major. They made an immediate impression with their debut for the label, 1993's Gentlemen, which served as a supremely effective calling card for their blues- and soul-influenced brand of darkly cinematic post-punk. It's a piece of work that was destined to remain outside the Top 40 mainstream, but that was never the point; this is an unfiltered cigarette of a record, one which ranks among the finest examples of how things occasionally went really right during the industry's yearslong frenzy for all things "alternative."

All that being said, I cannot tell a lie — my favorite Afghan Whigs moment is their cover of "Be for Real," the Frederick Knight classic first recorded by Marlena Shaw in 1976.

Basehead - The '90s "alternative" explosion is often portrayed as a corrective reaction against years of increasingly formulaic hair metal and melodic rock, but a lot of the music that came out of this era was hostile toward formula in general, particularly the arbitrarily drawn genre borders that generations of listeners took for granted. Cross-pollination between rock and hip-hop proved particularly fruitful, and although it would eventually become its own sort of stultifying formula, there was a time when this type of thing sounded like it could be the future.

Basehead, the group led by frontman, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist Michael Ivey, briefly seemed destined to lead that charge, but they were hamstrung by a couple of serious issues. First and perhaps most importantly, they signed with Imago, a black hole of a label whose greatest claims to fame are signing Paula Cole, giving slam poet Maggie Estep a hit-like thing with "Hey Baby," and being the first record company to bungle the release of an Aimee Mann solo album. Also less than helpful: After releasing 1993's Not in Kansas Anymore, Basehead took three years to return with Faith, a record that represented a pronounced shift toward Christian music. Not that Ivey's music was particularly commercial to begin with, but the number of artists who can take that type of hard left turn and count on the audience hanging on is extremely low.

Mary J. Blige - This is a weird pick, but only because Blige was already a big star by the time this issue was printed. Her first album, 1992's What's the 411?, was well on its way to quadruple-platinum status at this point, three singles deep into its impressive six-single run, so the staff at SPIN was going out on an extremely short limb by including her here. Toni Braxton was sitting right there, you guys.

Therapy? - In general, A&M's "alternative" signings in the '90s tended toward the mainstream; off the top of my head, I'm guessing their biggest winner during that era was probably the Gin Blossoms. The label wasn't entirely averse to taking long shots, however, as evidenced by their associations with volume-dealing acts like Therapy? and Paw.

If you prowled used CD bins during this era, you absolutely came across the Therapy? album Troublegum more times than you could count — and judging by its American sales figures, you probably never listened to it, and you certainly never bought it. I'm not here to shame you for this; while I applaud Therapy? for their longevity (26 years and counting!), their music strikes me as all volume and very little actual impact. Bash, shout, rinse, repeat.

Mad Cobra - With the exception of a few unexpected hits, the Top 40 has traditionally been fairly hostile toward dancehall artists — but it was the early '90s and all bets seemed to be off, so it isn't hard to understand why SPIN would waste a pick on Mad Cobra here. He was, after all, coming off a big fat hit single with 1992's "Flex," so there was reason to believe he'd build on that momentum, even though the song didn't do much for album sales, and follow-up singles failed to chart.

Long story short, Mad Cobra did not build on that momentum. His next LP, Goldmine, failed to chart, and although he continued to enjoy commercial success in Jamaica, his only other U.S. release of note is "Big Long John," a minor hit from 1996's Milkman LP. For the remainder of the decade, American pop listeners would have to get their tropical pop vibes from Shaggy, Big Mountain, and the annoyingly persistent UB40.

The Verve - Calling their music "desperately passionate," this issue's Verve writeup compares the band to the Rolling Stones, which turned out to be as accurate as it was darkly prescient. Volatile from the start, they earned some buzz behind their 1992 self-titled EP, built on it with 1993's A Storm in Heaven, and then broke up (for the first time) while 1995's A Northern Soul was in the midst of its Top 20 chart run in their native U.K. A quick reunion led to 1997's Urban Hymns, which produced the worldwide smash (and litigation magnet) "Bitter Sweet Symphony"; shortly thereafter, they broke up again. Yet another reunion led to the release of Forth in 2008, followed by their third and allegedly final breakup — but now that their old pals in Oasis are charging big bucks for their reunion tour, who knows?

Anyway, I think this stuff has held up reasonably well; even if the Verve weren't doing anything terribly unique, they were doing it with just the sort of self-obsessed swagger that turns ordinary citizens into rock stars... and then fuels lasting feuds that blow up bands. Sometimes more than once, if you're lucky.

Now, as promised, here's that collection of potential Next Big Things from artists who were already big in their own right. A more interesting and/or accurate list? See what you think: